(Welcome to part two of our mini-series on Vampyr. If you missed part one, you can find it here. Today we’ll be taking in the sights at the East End docks, meeting the colourful locals, and murdering our way through a warehouse or two.)

After messing around with the game’s upgrade system (I chose Bloodspear, by the way, because obviously I did), we’re forced once again to flee from Reid’s vampire-hunting pursuers. In the process we get our first real taste of the game’s combat system with the gloves off.

The combat in Vampyr is hardly a revelation – it works for what it is, and there’s enough variation that it doesn’t wear out its welcome for a good few hours. But Bloodborne it is trying to be, and Bloodborne it is not – for all its enemy variety and special attacks and weapon upgrades, it does eventually start to feel very samey.

Add to this the fact that every time we travel across the map we’ll encounter patrol after patrol of enemies, and it’s hard not to wish that Vampyr showed a bit more restraint. This game’s strengths are in other places – we shouldn’t have to go through fight after fight just to get to the interesting bits.

Fortunately, by now Reid has very nearly come round to the fact that he’s obviously a vampire.

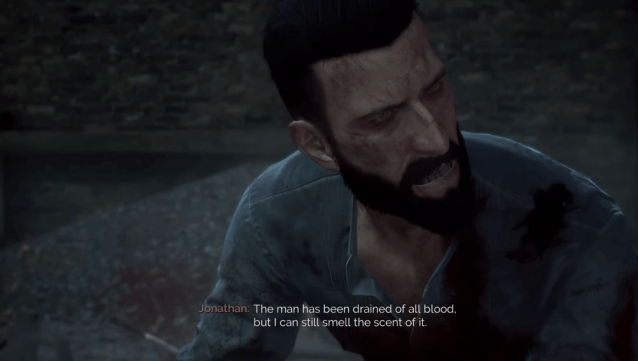

That’s grumbling for later in the game, though. For now, having made it across the Thames, we find a corpse on the riverbank – one completely drained of blood. Guessing that this might be the work of the vampire who created us, we make our way through the deserted streets to our first sign of civilisation – the Turquoise Turtle Pub.

It’s here that we meet the first people we don’t immediately fight and/or eat. First there’s Tom the pub owner, who’s only moderately concerned about our wild-eyed, blood-stained appearance. He tells us a little about a recent string of murders, and lets us know that someone (possibly the vampire we’re looking for?) is staying upstairs.

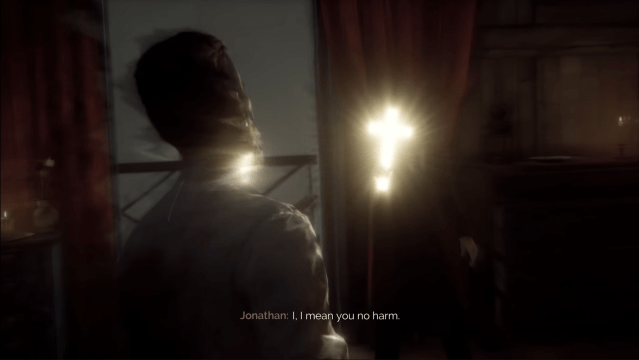

After heading up to confront this mystery person/vampire, we overhear a man and a woman arguing in one of the rooms. The woman – obviously a vampire, and an incautious one at that – eventually senses us listening to their very loud conversation about her being a vampire, and flees into the night. The man invites us in, and when we enter we’re stopped in our tracks by a burning crucifix.

Vampire Lore #3: religious symbols = bad.

The sudden shock of the crucifix wracking us with crippling pain, the haunting music that suddenly kicks in, and the skillful voice acting of both Reid and his mystery interlocutor combine to make this moment another 10/10 Vampyr cutscene.

This man, who we soon find out to be one Dr. Edgar Swansea (the poshest man alive), is not our vampire creator, nor even a vampire at all. He’s just a kind of vampire enthusiast. He’s also understandably suspicious of us. But after a while he puts down his crucifix and we have a chat.

It turns out he’s also investigating the recent string of murders, and while he isn’t quite ready to trust us, he wishes us luck with our search. With this we head back down to the pub to interrogate the locals, and to try to find the location of the murderer.

We talk to Dyson – the local drunk, who’s rude and unhappy, and really not much help. Next, there’s Sabrina – the pub’s waitress, who really just wants to get rid of us. But she does tell us about William Bishop – a local who recently showed up sick, and acting erratically. She tells us to ask Tom for more information.

Dr. Swansea is the best. I can’t decide if he’s going to betray me for some reason later in the game.

The dialogue in Vampyr is one of the main pillars of the game, and mostly does what it’s trying to do very well. Whereas most RPGs tend to focus on a small number of well-fleshed out characters, Vampyr goes all out on its most minor NPCs, with a frankly staggering cast of well-written, (mostly) well-acted characters to converse with.

The most impressive thing is how good a job the game’s writers do of capturing an NPC’s personality (and laying out an interesting backstory, for each), considering quite how many hours of in-depth (mostly optional) conversations the player can have with quite so many NPCs.

Vampyr is definitely helped by its real-world setting here – it’s far easier to make me care about a depressed, shell-shocked veteran of World War One than it is to make me care about a depressed, fantasy-shell-shocked veteran of the Great Dragon War – but the writers shouldn’t be given short shrift – this is really good stuff.

At this point we can also peruse the game’s various menus. This is the Citizen Menu. It tells you which citizens are still alive, and which have ended up on your menu.

What’s not so stellar is the nuts and bolts of the game’s dialogue system itself. While the lines themselves are generally strong, the connective tissue holding them together is a tad weak. Most of what you actually do boils down to clicking an ‘ask about [topic]’ button for every topic until you’ve heard everything the NPC has to say.

There are also surprisingly few points where you can respond with an opinion of your own, and when these moments are present they’re often just slightly too vague to really know what you’re choosing to say.

The dialogue also doesn’t flow as well as it could. You’ll spend a lot of time switching between conversation topics, and it feels awkward and unnatural every single time. Here’s a made-up example of what I mean:

NPC: “I guess I just couldn’t get over my father’s death, and I certainly couldn’t be there for my sister in the way she needed me to be. One day I just kind of…left. I wandered around for a few years, ran out of money, and eventually wound up here.”

Player: “I heard there were some murders around town – can you tell me anything about that?”

Here’s a screen showing Tom Watts’ BLOOD QUALITY. More on that in Part Three.

This is a problem basically every game developer struggles with. Well, every game developer except Inkle (makers of 80 Days and the Sorcery! series). In my book Inkle write the best dialogue in games, in part because they have a system for varying lines of dialogue based on when they’re being said. So for the example above, the game would check ‘is this line of player dialogue being said as part of a related conversation, or apropos of nothing? If it’s the latter, preface it with something like ‘Interesting. Oh, by the way…’

You can watch a great talk about Inkle’s Jon Ingold talking about how they do this here. It’s great stuff. But while I wish every developer could do what Inkle does with dialogue, it’s not vital. And not only does it take time, effort, and skill to fix these minor problems – it also very expensive to do when all your dialogue is voice acted. Probably prohibitively expensive for a mid-budget game like Vampyr.

THIS WEEK’S INSIGHTFUL GAME DESIGN LESSON:

Writing game dialogue is a labyrinthine nightmare where the best-written line of dialogue can fall on its arse for any number of tiny, barely-related reasons. Add the constraints of voice acting into the mix and we can all agree that it’s better to never try, lest we risk falling short of perfection.

I actually don’t remember this man. I think he was already murdered before I got here.

We use our vampire mind powers (yes, we have them now, btw) to bully Tom into telling us more about William Bishop, and after doing some light investigation along the docks we track him down to an abandoned warehouse that just screams ‘IMMINENT BOSS FIGHT’. There are skeletons hanging from the ceiling, for god’s sake.

William Bishop (who appears to be some kind of zombie-vampire sub-species) is feeding on a man called Sean Hampton who’s somehow still alive. We confront Bishop in a very paint-by-numbers boss fight – dodge, stun, attack, try not to die. And in classic action film fashion, the apparently defeated Bishop gets the drop on us when our back is turned, and we’re saved just in the nick of time by…the mysterious vampire woman we overheard in the pub. She helpfully avoids telling us anything, then leaves.

Finally, Dr. Swansea enters triumphantly in a lovely little steam boat, and whisks us (and a babbling, worse-for-wear Sean Hampton) away to safety. We (the player) find out that Reid is actually a famous medical researcher (presumably Reid already knew that), and Dr. Swansea offers us a job at the nearby Pembroke Hospital.

This will let us stay safe and inconspicuous (working the night shift, of course) while we continue looking for our creator. Hopefully we’ll get a chance to take on the epidemic sweeping through the city at some point, too.

We’ll explore Pembroke Hospital in Part Three. For now, though – as always, you can follow me on Twitter by clicking here. Also, my very own (in-development) text-based monster-hunting RPG – The Red Market – can be played online here for the low, low price of zero pounds.

Dr. Swansea to the rescue in his lovely steam boat.